Blunt Abdominal Trauma, Evaluation of

Archived PMG

Published 2002

Citation: J Trauma. 53(3): 602-615, September 2002.

Authors

EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group

William S. Hoff, MD, Brandywine Hospital, Coatesville, PA

Michelle Holevar, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Chicago, IL

Kimberly K. Nagy, MD, Cook County Hospital and Rush University, Chicago, IL

Lisa Patterson, MD, Wright State University, Dayton, OH

Jeffrey S. Young, MD, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA

Abenamar Arrillaga, MD, Greenville Memorial Hospital, Greenville, SC

Michael P. Najarian, DO, Lehigh Valley Hospital, Allentown, PA

Carl P. Valenziano, MD, Morristown Memorial Hospital, Morristown, NJ

Address for correspondence

William S. Hoff, MD, FACS

Brandywine Hospital—Department of Traumatology

201 Reeceville Road Coatesville, PA 19320

Phone: (610) 383-8099 / Fax: (610) 383-8352

E-mail: bill.hoff@uphs.upenn.edu

I. Statement of the problem

Evaluation of patients who have sustained blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) may pose a significant diagnostic challenge to the most seasoned trauma surgeon. Blunt trauma produces a spectrum of injury from minor, single-system injury to devastating, multi-system trauma. Trauma surgeons must have the ability to detect the presence of intra-abdominal injuries across this entire spectrum. While a carefully performed physical examination remains the most important method to determine the need for exploratory laparotomy, there is little Level I evidence to support this tenet. In fact, several studies have highlighted the inaccuracies of the physical examination in BAT.[1][2] The effect of altered level of consciousness as a result of neurologic injury, alcohol or drugs, is another major confounding factor in assessing BAT.

Due to the recognized inadequacies of physical examination, trauma surgeons have come to rely on a number of diagnostic adjuncts. Commonly used modalities include diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) and computed tomography (CT). Although not available universally, focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) has recently been included in the diagnostic armamentarium. Diagnostic algorithms outlining appropriate use of each of these modalities individually have been established. Several factors influence the selection of diagnostic testing: (1) type of hospital—i.e., trauma center vs. “non-trauma” hospital; (2) access to a particular technology at the surgeon’s institution; (3) the surgeon’s individual experience with a given diagnostic modality. As facilities evolve, technologies mature and surgeons gain new experience, it is important that any diagnostic strategy constructed be dynamic.

The primary purpose of this study was to develop an evidence-based, systematic diagnostic approach to BAT utilizing the three major diagnostic modalities: i.e., DPL, CT and FAST. This diagnostic regimen would be designed such that it could be reasonably applied by all general surgeons performing an initial evaluation of BAT.

II. Process

A. Identification of references

A MEDLINE search was performed using the key words “abdominal injuries”and thesubheading“diagnosis”. This search was limited further to (1) clinical research, (2) published in English, (3) publication dates January 1978 through February 1998. The initial search yielded 742 citations. Case reviews, review articles, meta- analyses, editorials, letters to the editor, technologic reports, pediatric series and studies involving a significant number of penetrating abdominal injuries were excluded prior to formal review. Additional references, selected by the individual subcommittee members, were then included to compile the master reference list of 197 citations.

B. Quality of the references

Articles were distributed among subcommittee members for formal review. A review data sheet was completed for each article reviewed which summarized the main conclusions of the study, and identified any deficiencies in the study. Further, reviewers classified each reference by the methodology established by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as follows:

Class I: Prospective, randomized, double-blinded study Class II: Prospective, randomized, non-blinded trial Class III: Retrospective series, meta-analysis Following review by the subcommittee, references were excluded based on poor

design or invalid conclusions. An evidentiary table was constructed using the remaining 101 references: Class I (20); Class II (32); Class III (49). Recommendations were based on studies included in the evidentiary table.

III. Recommendations

A. Level I

- Exploratory laparotomy is indicated for patients with a positive DPL.

- CT is recommended for the evaluation of hemodynamically stable patients with equivocal findings on physical examination, associated neurologic injury, or multiple extra-abdominal injuries. Under these circumstances, patients with a negative CT should be admitted for observation.

- CT is the diagnostic modality of choice for nonoperative management of solid visceral injuries.

- In hemodynamically stable patients, DPL and CT are complementary diagnostic modalities.

B. Level II

- FAST may be considered as the initial diagnostic modality to exclude hemoperitoneum. In the presence of a negative or indeterminate FAST result, DPL and CT have complementary roles.

- When DPL is used, clinical decisions should be based on the presence of gross blood on initial aspiration (i.e., 10 ml) or microscopic analysis of lavage effluent.

- In hemodynamically stable patients with a positive DPL, follow-up CT scan should be considered, especially in the presence of pelvic fracture or suspected injuries to the genitourinary tract, diaphragm or pancreas.

- Exploratory laparotomy is indicated in hemodynamically unstable patients with a positive FAST. In hemodynamically stable patients with a positive FAST, follow-up CT permits nonoperative management of select injuries.

- Surveillance studies (i.e., DPL, CT, repeat FAST) are required in hemodynamically stable patients with indeterminate FAST results.

C. Level III

- Objective diagnostic testing (i.e., FAST, DPL, CT) is indicated for patient with abnormal mentation, equivocal findings on physical examination, multiple injuries, concomitant chest injury or hematuria.

- Patients with seatbelt sign (SBS) should be admitted for observation and serial physical examination. Detection of intraperitoneal fluid by FAST or CT in a patient with SBS mandates either DPL to determine the nature of the fluid or exploratory laparotomy.

- CT is indicated for the evaluation of suspected renal injuries.

- A negative FAST should prompt follow-up CT for patients at high risk for intraabdominal injuries (e.g., multiple orthopedic injuries, severe chest wall trauma, neurologic impairment).

- Splanchnic angiography may be considered in patients who require angiography for the evaluation of other injuries (e.g., thoracic aortic injury, pelvic fracture).

IV. Scientific Foundation

A. Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL)

DPL was introduced by Root in 1965 as a rapid and accurate method to identify the presence of intra-abdominal hemorrhage following trauma.[3] Subsequent studies have confirmed the efficacy of DPL in diagnosing abdominal hemorrhage as well as its superiority over physical examination alone.[4] The accuracy of DPL has been reported between 92% and 98%.[5][6][7][8][9][10] The high sensitivity of DPL is due to the significant false positive rate of the technique.[11][12][13] Several authors have highlighted the importance of interpreting DPL results in the context of the overall clinical condition of the patient. A positive DPL does not necessarily mandate immediate laparotomy in the hemodynamically stable patient.[12][14][15][16] DPL has been shown to be more efficient than CT scan in identifying patients that require surgical exploration.[17]

The complication rate associated with DPL is quite low.[18] The incidence of complications is lower for open DPL compared with to the closed technique. However, closed DPL can be performed more rapidly.[19][20][21][22] Studies designed to examine the ability of physicians to estimate the red blood cell (RBC) count in DPL fluid have demonstrated the poor sensitivity of visual inspection.[23][24][25] A positive DPL, based on microscopic analysis of lavage fluid, has been defined as > 105 RBC/mm3. It has been recommended that patients with RBC counts in the equivocal range (i.e., 25,000–75,000 RBC/mm3) undergo additional diagnostic testing, such as CT scanning.[12]

The false positive rate for DPL is increased in patients with pelvic fractures.[26][27] In order to avoid sampling the retroperitoneal hematoma, a suprpa-umbilical approach has been recommended, theoretically reducing the chances of a false positive result.[28]

The advantages of DPL for detection of hollow visceral injuries have been clearly demonstrated.[29][30] Two studies which advocate analysis of DPL fluid for amylase and alkaline phosphatase consistent with enteric injuries have been disputed.[31][32][33] Similarly, the utility of the DPL white blood cell (WBC) count has been questioned.[34][35][36] DPL is sensitive for mesenteric injury and, in fact, has been shown to be superior to CT for the diagnosis of this injury.[37]

Thus, DPL is a safe, rapid and accurate method for determining the presence of intraperitoneal blood in victims of BAT. It is more accurate than CT for the early diagnosis of hollow visceral and mesenteric injuries, but it does not reliably exclude significant injuries to retroperitoneal structures. False positive results may occur in the presence of pelvis fractures. Hemodynamically stable patients with equivocal results are best managed by additional diagnostic testing to avoid unnecessary laparotomies.

B. Computed Tomography (CT)

Routine use of CT for the evaluation of BAT was not initially viewed with overwhelming enthusiasm. CT requires a cooperative, hemodynamically stable patient. In addition, the patient must be transported out of the trauma resuscitation area to the radiographic suite. Specialized technicians and the availability of a radiologist for interpretation were also viewed as factors which limited the utility of CT for trauma patients. CT scanners are now available in most trauma centers and, with the advent of helical scanners, scan time has been significantly reduced. As a result, CT has become an accepted part of the traumatologist’s armamentarium.

The accuracy of CT in hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients has been well established. Sensitivity between 92% and 97.6% and specificity as high as 98.7% has been reported in patients subjected to emergency CT.[38][39] Most authors recommend admission and observation following a negative CT scan.[40][41] In a recent study of 2774 patients, the authors concluded that the negative predictive value (99.63%) of CT was sufficiently high to permit safe discharge of BAT patients following a negative CT scan.[42]

CT is notoriously inadequate for the diagnosis of mesenteric injuries and may also miss hollow visceral injuries. In patients at risk for mesenteric or hollow visceral injury, DPL is generally felt to be a more appropriate test.[37][43] A negative CT scan in such a patient cannot reliably exclude intra-abdominal injuries.

CT has the unique ability to detect clinically unsuspected injuries. In a series of 444 patients in whom CT was performed to evaluate renal injuries, 525 concomitant abdominal and/or retroperitoneal injuries were diagnosed. Another advantage of CT scanning over other diagnostic modalities is its ability to evaluate the retroperitoneal structures.[40] Kane performed CT in 44 hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients following DPL. In 16 patients, CT revealed significant intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries not diagnosed by DPL. Moreover, the findings on CT resulted in a modification to the original treatment plan in 58% of the patients.[44]

C. Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma (FAST)

In recent years, focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) has emerged as a useful diagnostic test in the evaluation of BAT. The advantages of the FAST examination have been clearly established. FAST is noninvasive, may be easily performed and can be done concurrently with resuscitation. In addition, the technology is portable and may be easily repeated if necessary.[45][46][47][48] In most cases, FAST may be completed within 3 or 4 minutes.[49][50][51] The test is especially useful for detecting intra-abdominal hemorrhage in the multiply injured or pregnant patient.[52]

A noted drawback to the FAST examination is the fact that a positive examination relies on the presence of free intraperitioneal fluid. In the hands of most operators, ultrasound will detect a minimum of 200 mL of fluid.[53] Injuries not associated with hemoperitoneum may not be detected by this modality.[49][54][55] Thus, ultrasound is not a reliable method for excluding hollow visceral injury.[47][49][56][57][58] In addition, the FAST examination cannot be used to reliably grade solid organ injuries. Therefore, in the hemodynamically stable patient, a follow-up CT scan should be obtained if nonoperative management is contemplated.[59]

FAST compares favorably with more traditionally utilized diagnostic tests. In the hemodynamically stable patient with BAT, FAST offers a viable alternative to DPL.[60] DPL may also be used as a complementary examination in the hemodynamically stable patient in the presence of an equivocal or negative ultrasound with strong clinical suspicion of visceral injury.[61][62] FAST has demonstrated utility in hemodynamically stable patients with BAT.[58][60][63] In addition, ultrasound has been shown to be more cost-effective when compared to DPL or CT.[45][47][60]

Overall, FAST has a sensitivity between 73% and 88%, a specificity between 98% and 100% and is 96% to 98% accurate.[46][50][57][58][64][65] This level of accuracy is independent of the practitioner performing the study. Surgeons, emergency medicine physicians, ultrasound technicians and radiologists have equivalent results.[46][53][64][65][66]

D. Other Diagnostic Modalities

As interest in laparoscopic procedures has increased among general surgeons, there has been speculation regarding the role of diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) in the evaluation of BAT. One of the potential benefits postulated is the reduction of nontherapeutic laparotomies. With modification of the technique to include smaller instruments, portable equipment and local anesthesia, DL may be a useful tool in the initial evaluation of BAT. Although there are no randomized, controlled studies comparing DL to more commonly utilized modalities, experience at one institution using minilaparoscopy demonstrated a 25% incidence of positive findings on DL, which were successfully managed nonoperatively and would have resulted in nontherapeutic laparotomies.[67]

Although its ultimate role remains unclear, another modality to be considered in the diagnostic evaluation of BAT is visceral angiography. This modality may have diagnostic value when employed in conjunction with angiography of the pelvis or chest, or when other diagnostic studies are inconclusive.[68]

V. Summary

Injury to intra-abdominal viscera must be excluded in all victims of BAT. Physical examination remains the initial step in diagnosis but has limited utility under select circumstances. Thus, various diagnostic modalities have evolved to assist the trauma surgeon in the identification of abdominal injuries. The specific tests selected are based on the clinical stability of the patient, the ability to obtain a reliable physical examination and the provider’s access to a particular modality. It is important to emphasize that many of the diagnostic tests utilized are complementary rather than exclusionary.

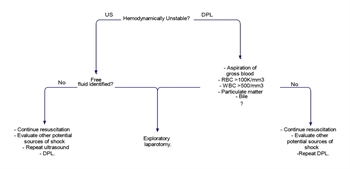

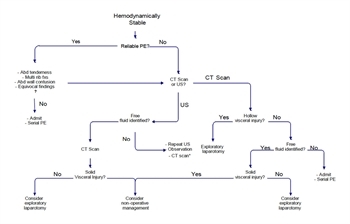

Based on the above recommendations, a reasonable diagnostic approach to BAT is summarized in Figures 1 and 2. In hemodynamically stable patients with a reliable physical examination, clinical findings may be used to select patients who may be safely observed. In the absence of a reliable physical examination, the main diagnostic choice is between CT or FAST (with CT in a complementary role). Hemodynamically unstable patients may be initially evaluated with FAST or DPL.

VI. Future Investigation

Recent literature is replete with studies that emphasize the many advantages of ultrasound in the valuation of BAT. Although this technology is becoming more available to trauma surgeons, for a variety of reasons, it has not become universally available in all centers. Continued research addressing the utility of FAST, with emphasis on its advantages specific to resource utilization, is suggested. In addition, studies should be designed to more closely evaluate the feasibility of FAST as the sole diagnostic test in hemodynamically stable patients. Perhaps safe strategies for nonoperative management of solid visceral injuries could be developed which rely on FAST alone, such that the number of CT scans could be reduced.

VII. References

- Rodriguez A, DuPriest RW Jr., Shatney CH: Recognition of intra-abdominal injury in blunt trauma victims. A prospective study comparing physical examination with peritoneal lavage. Am Surg 48: 457–459, 1982.

- Schurink GW, Bode PJ, van Luijt PA, et al: The value of physical examination in the diagnosis of patients with blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study. Injury 28: 261–265, 1997.

- Root HD, Hauser CW, McKinley CR, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Surg 57: 633–637, 1965.

- Bivins BA, Sachatello CR, Daughtery ME, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is superior to clinical evaluation in blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surg 44: 637–641, 1978.

- Smith SB, Andersen CA: Abdominal trauma: the limited role of peritoneal lavage. Am Surg 48: 514–517, 1982.

- Henneman PL, Marx JA, Moore EE, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: accuracy in predicting necessary laparotomy following blunt and penetrating trauma. J Trauma 30: 1345–1355, 1990.

- Krausz MM, Manny J, Austin E, et al: Peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. SG & O 152: 327–330, 1981.

- MooreJB, Moore EE, Markivchick VJ, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage for abdominal trauma: superiority of the open technique at the infraumbilical ring. J Trauma 21: 570–572, 1981.

- Jacob ET, Cantor E: Discriminate diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal injuries: accuracy and hazards. Am Surg 45: 11–14, 1979.

- Fischer RP, Beverlin BC, Engrav LH, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: fourteen years and 2586 patients later. Am J Surg 136: 701–704, 1978.

- Bilge A, Sahin M: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. Eur J Surg 157: 449–451, 1991.

- DeMaria EJ: Management of patients with indeterminate diagnostic peritoneal lavage results following blunt trauma. J Trauma 31: 1627–1631, 1991.

- Van Dongen LM, de Boer HH: Peritoneal lavage in closed abdominal injury. Injury 16: 227–229, 1985.

- Day AC, Rankin N, Charlesworth P: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: integration with clinical information to improve diagnostic performance. J Trauma 32: 52–57, 1992.

- Barba C, Owen D, Fleiszer D, et al: Is positive diagnostic peritoneal lavage an absolute indication for laparotomy in all patients with blunt trauma? The Montreal General Hospital experience. Can J Surg 34: 442–445, 1991.

- Drost TF, Rosemurgy AS, Kearney RE, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Limited indications due to evolving concepts in trauma care. Am Surg 57: 126–128, 1991.

- Blow O, Bassam D, Butler K, et al: Speed and efficiency in the resuscitation of blunt trauma patients with multiple injuries: the advantage of diagnostic peritoneal lavage over abdominal computerized tomography. J Trauma 44: 287–290, 1998.

- Davis JW, Hoyt DB, Mackersie RC, et al: Complications in evaluating abdominal trauma: diagnostic peritoneal lavage versus computerized axial tomography. J Trauma 30: 1506–1509, 1990.

- Lopez-Viego MA, Mickel TJ, Weigelt JA: Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the evaluation of abdominal trauma. Am J Surg 160: 594–597, 1990.

- Cue JI, Miller FB, Cryer HM,III, et al: A prospective, randomized comparison between open and closed peritoneal lavage techniques. J Trauma 30: 880–883, 1990.

- Wilson WR, Schwarcz TH, Pilcher DB: A prospective randomized trial of the Lazarus-Nelson vs. the standard peritoneal dialysis catheter for peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 27: 1177–1180, 1987.

- Felice PR, Morgan AS, Becker DR: A prospective randomized study evaluating periumbilical versus infraumbilical peritoneal lavage: a preliminary report. A combined hospital study. Am Surg 53: 518–520, 1987.

- Gow KW, Haley LP, Phang PT, et al: Validity of visual inspection of diagnostic peritoneal lavage fluid. Can J Surg 39: 114–119, 1996.

- Wyatt JP, Evans RJ, Cusack SP: Variation among trainee surgeons in interpreting diagnostic peritoneal lavage fluid in blunt abdominal trauma. J Royal Coll Surg (Edin) 37: 104–106, 1992.

- Driscoll P, Hodgkinson D, Mackway-Jones K: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: It’s red but is it positive? Injury 23: 267–269, 1992.

- Mendez C, Gubler KD, Maier RV: Diagnostic accuracy of peritoneal lavage in patients with pelvic fractures. Arch Surg 129: 477–482, 1994.

- Hubbard SG, Bivins BA, Sachatello CR, et al: Diagnostic errors with peritoneal lavage in patients with pelvic fractures. Arch Surg 114: 844–846, 1979.

- Cochran W, Sobat WS: Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage. A multiphasic prospective randomized comparison. Ann Surg 200: 24–28, 1984.

- Meyer DM, Thal ER, Weigelt JA, et al: Evaluation of computed tomography and diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 29: 1168–1170, 1989.

- Burney RE, Mueller GL, Coon WW, et al: Diagnosis of isolated small bowel injury following blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 12: 71–74, 1983.

- McAnena OJ, Marx JA, Moore EE: Peritoneal lavage enzyme determinations following blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma 31: 1161–1164, 1991.

- McAnena OJ, Marx JA, Moore EE: Contributions of peritoneal lavage enzyme determinations to the management of isolated hollow visceral abdominal injuries. Ann Emerg Med 20: 834–837, 1991.

- Megison SM, Weigelt JA: The value of alkaline phosphatase in peritoneal lavage. Ann Emerg Med 19: 503–505, 1990.

- D’Amelio LF, Rhodes M: A reassessment of peritoneal lavage leukocyte count in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 30: 1291–1293, 1990.

- Soyka JM, Martin M, Sloan EP, et al: Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: is an isolated WBC count greater that or equal to 500/mm3 predictive of intra-abdominal injury requiring celiotomy in blunt trauma patients? J Trauma 30: 874–879, 1990.

- Jacobs DG, Angus L, Rodriguez A, et al: Peritoneal lavage white count: a reassessment. J Trauma 30: 607–612, 1990.

- Ceraldi CM, Waxman K: Computerized tomography as an indicator of isolated mesenteric injury. A comparison with peritoneal lavage. Am Surg 56: 806–810, 1990.

- Peitzman AB, Makaroun MS, Slasky BS, et al: Prospective study of computed tomography in initial management of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 26: 585–592, 1986.

- Webster VJ: Abdominal trauma: Pre-operative assessment and postoperative problems in intensive care. Anaest Int Care 13: 258–262, 1985.

- Lang EK: Intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal organ injuries diagnosed on dynamic computed tomograms obtained for assessment of renal trauma. J Trauma 30: 1161–1168, 1990.

- Matsubara TK, Fong HM, Burns CM: Computed tomography of abdomen (CTA) in management of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 30: 410–414, 1990.

- Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Passannante MR, et al: Admission or observation is not necessary after a negative abdominal computed tomographic scan in patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma: Results of a prospective, multi-institutional trial. J Trauma 44: 272–282, 1998.

- Nolan BW, Gabram SG, Schwartz RJ, et al: Mesenteric injury from blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surg 61: 501–506, 1995.

- Kane NM, Dorfman GS, Cronan JJ: Efficacy of CT following peritoneal lavage in abdominal trauma. J Comp Asst Tomo 11: 998–1002, 1987.

- Branney SW, Moore EE, Cantrill SV, et al: Ultrasound based key clinical pathway reduces the use of hospital resources for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 42: 1086–1090, 1997.

- Healey MA, Simons RK, Winchell RJ, et al: A prospective evaluation of abdominal ultrasound in blunt trauma: Is it useful? J Trauma 40: 875–883, 1996.

- Glaser K, Tschmelitsch J, Klingler P, et al: Ultrasonography in the management of blunt abdominal and thoracic trauma. Arch Surg 129: 743–747, 1994.

- Liu M, Lee CH, P’eng FK: Prospective comparison of diagnostic peritoneal lavage, computed tomographic scanning, and ultrasonography for the diagnosis of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 35: 267–270, 1993.

- Boulanger BR, McLellan BA, Brenneman FD, et al: Emergent abdominal sonography as a screening test in a new diagnostic algorithm for blunt trauma. J Trauma 40: 867–874, 1996.

- Boulanger BR, Brenneman FD, McLellan BA, et al: A prospective study of emergent abdominal sonography after blunt trauma. J Trauma 39: 325–330, 1995.

- Ma OJ, Kefer MP, Mateer JR, et al: Evaluation of hemoperitoneum using a singlevs. multiple-view ultrasonographic examination. Acad Emerg Med 2: 581–586, 1995.

- Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Jaffin JH, et al: Prospective evaluation of surgeons’ use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients. J Trauma 34: 516–527, 1993.

- Branney SW, Wolfe RE, Moore EE, et al: Quantitative sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid. J Trauma 39: 375–380, 1995.

- Sherbourne CD, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, et al: Visceral injury without hemoperitoneum: a limitation of screening abdominal songography for trauma. Emerg Radiol 4: 349–354, 1997.

- Tso P, Rodriguez A, Cooper C: Sonography in blunt abdominal trauma: a preliminary progress report. J Trauma 33: 39–44, 1992.

- Buzzas GR, Kern SJ, Smith RS, et al: A comparison of sonographic examinations for trauma performed by surgeons and radiologists. J Trauma 44: 604–608, 1998.

- Smith SR, Kern SJ, Fry WR, et al: Institutional learning curve of surgeon-performed trauma ultrasound. Arch Surg 133: 530–536, 1998.

- McKenney MG, Martin L, Lentz K, et al: 1000 consecutive ultrasounds for blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 40: 607–612, 1996.

- Chambers JA, Pilbrow WJ: Ultrasound in abdominal trauma: an alternative to peritoneal lavage. Arch Emerg Med 5: 26–33, 1988.

- McKenney KL, McKenney MG, Nunez DB, et al: Cost reduction using ultrasound in blunt abdominal trauma. Emerg Radiol 4: 3–6, 1997.

- Kimura A, Otsuka T: Emergency center ultrasonography in the evaluation of hemoperitoneum: A prospective study. J Trauma 31: 20–23, 1991.

- Gruessner R, Mentges B, Duber C, et al: Sonography versus peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 29: 242–244, 1989.

- Rothlin MA, Naf R, Amgwerd M, et al: Ultrasound in blunt abdominal and thoracic trauma. J Trauma 34: 488–495, 1993.

- Kern SJ, Smith RS, Fry WR, et al: Sonographic examination of abdominal trauma by senior surgical residents. Am Surg 63: 669–674, 1997.

- Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, Schmidt JA, et al: A prospective study of surgeon-performed ultrasound as the primary adjuvant modality for injured patient assessment. J Trauma 39: 492–500, 1995.

- McKenney M, Lentz K, Nunez D, et al: Can ultrasound replace diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the assessment of blunt trauma? J Trauma 37: 439–441, 1994.

- Berci G, Sackier JM, Paz-Partlow M: Emergency laparoscopy. Am J Surg 161: 332335, 1991.

- Ward RE: Study and management of blunt trauma in the immediate post-impact period. Rad Clin NA 19: 3–7, 1981.

Tables

| First author | Year | Reference title | Class | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivins BA | 1978 |

Diagnostic exploratory celiotomy: an outdated concept in blunt abdominal trauma. South Med J 72: 969–970 |

I | Clinical evaluation alone would have missed 59% of injuries in blunt trauma patients studied. Exploratory laparotomy reco mmended for (+)DPL. Due to recognized false negative rate, admission and observation recommended for patients with (-)DPL. |

| Moore JB | 1980 |

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage for abdominal trauma: superiority of the open technique at the infraumbilical ring. J Trauma 21: 570–572 |

I | Open DPL preferred over closed. Increased time required for open DPL compensated by higher reliability. |

| Krausz MM | 1981 | Peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. S,G & O 152: 327–330 |

I | Laboratory study demonstrates safety and reliabi lity of percutaneous (closed) method of DPL. Clinical series documents percutaneous technique to be accurate in the diagnosis of visceral injury and/or hemoperitoneum. |

|

Cochran W |

1984 | Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage. A multiphasic prospective randomized comparison. Ann Surgery 200: 24–28 | I | No significant difference in accuracy between two techniques. Supraumbilical approach more accurate in presence of pelvis fracture. Complication rate higher with open DPL. |

| Felice PR | 1987 | A prospective randomized study evaluating periumbilical versus infraumbilical peritoneal lavage: a preliminary report. A combined hospital study.Am Surgeon 53: 518–520 | I | Periumbilical peritoneal lavage performed faster and preferred by majority of providers. Safety and sensitivity equivalent between the two techniques. |

| Wilson WR | 1987 | A prospective randomized trial of the Lazarus -Nelson vs the standard peritoneal dialysis catheter for peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 27: 1177–1180 | I | Percutaneous DPL (i.e. Lazarus -Nelson) associated with decreased time to catheter insertion with no significant difference in time to complete lavage, volume of fluid recovered, sensitivity, or specificity compared with open technique. Open DPL recommended for patient s with previous abdominal surgery or when percutaneous DPL unsuccessful. |

| Buechter KJ | 1990 | The use of serum amylase and lipase in evaluating and managing blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surgeon 56: 204–208 | I | Serum amylase and lipase are randomly elevated in BAT population. Diagnostic testing is not warranted based on elevated amylase or lipase on initial evaluation. |

| Howdieshell TR | 1989 | Open versus closed peritoneal lavage with particular attention to time, accuracy, and cost.Am J Emerg Med 7: 367–371 | I | Closed DPL is faster, safer and equally accurate as open DPL. |

| Kimura A | 1991 | Emergency center ultrasonography in the evaluation of hemoperitoneum: a prospective study.J Trauma 31: 20–23 | I | Recommend US as a screening modality for detection of hemoperitoneum (86. 7% sensitivity; 100% specificity). DPL indicated for neurologically injured patients with ( -)US and a high suspicion of visceral injury. |

| Troop B | 1991 | Randomized, prospective comparison of open and closed peritoneal lavage for abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 20: 1290–1292 | I | Closed DPL superior to open DPL. Open or semi -open technique recommended for patients in whom closed DPL is contraindicated. |

| Day AC | 1992 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: integration with clinical information to improve diagnostic perform ance.J Trauma 32: 52–57 | I | Combination of clinical evaluation and DPL reduces rate of non -therapeutic laparotomies, but increases the number of missed injuries. The highest accuracy (95%) is obtained by combination of circulatory assessment and DPL. |

| Tso P | 1992 | Sonography in blunt abdominal trauma: a preliminary progress report.J Trauma 33: 39–44 | I | US sensitive (91%) for detection of free fluid but less sensitive (69%) for identification of free fluid plus organ disruption. US does not rule out organ inj ury in the absence of hemoperitoneum. |

| Liu M | 1993 | Prospective comparison of diagnostic peritoneal lavage, computed tomographic scanning, and ultrasonography for the diagnosis of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 35: 267–270 | I | Sensitiviy and specificity of U S is comparable to CT or DPL. False negatives identified using CT (1) and US (3) in the presence of intestinal perforations. Defined complementary roles of US, CT and DPL in evaluation of BAT. |

| Rothlin MA | 1993 | Ultrasound in blunt abdominal and thoracic t rauma. J Trauma 34: 488–495 | I | US highly sensitive (98.1%) and specific (100%) for identification of intra-abdominal fluid. Specificity remains high (99.6%) but sensitivity decreases (43.6%) for diagnosis of specific organ lesions. Recommend 1) CT to iden tify specific organ injury, 2) serial US every 1 -2 hrs for first 6 hrs, then every 12 hrs for 2 days. |

| Rozycki GS | 1993 | Prospective evaluation of surgeons” use of ultrasound in the evaluation of trauma patients.J Trauma 34: 516–527 | I | In mixed blunt (84%) / penetrating (16%) population, US has 79.0% sensitivity and 95.6% specificity. Adjusted sensitivity for blunt trauma is 84.0%. US indicated for 1) blunt thoracoabdominal injury; 2) suspected pericardial tamponade; 3) multi -system injruy with unknown etio logy of hypotension; 4) pregnant trauma patient. |

| Goletti O | 1994 | The role of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma: results in 250 consecutive cases. J Trauma 36: 178–181 | I | Overall sensitivity of US 86.7%. Intraperitoneal fluid volumes ? 250 ml correl ates with high unnecessary laparotomy rate when diagnosed by US; suggest 250 ml as threshold for non -operative management using US. US -guided parascentesis allows safe non -operative management in presence of small volume of fluid. |

| Huang M | 1994 | Ultasonogr aphy for the evaluation of hemoperitoneum during resuscitation: a simple scoring system.J Trauma 36: 173–177 | I | US 100% specific for diagnosis of hemoperitoneum. Scoring system developed to predict presence of hemoperitoneum and need for surgery; US score ? 3 corresponds to > 1000 ml blood with 84% sensitivity, 71% specificity and 71% accuracy. |

| McKenney M | 1994 | Can ultrasound replace diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the assessment of blunt trauma? J Trauma 37: 439–441 | I | Comparison of US with DPL, CT scan a nd exploratory laparotomy in 200 patients with BAT. US 83% sensitive, 100% specific and 97% accurate. |

| Branney SW | 1995 | Quantitative sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting free intraperitoneal fluid.J Trauma 39: 375–380 | I | Prospective study of US performed in patients following DPL with no aspiration of gross blood. US demonstrated 97% sensitivity and detected mean fluid volume of 619 ml. US screen should be initial branch point in BAT algorithm. |

| Rozycki GS | 1995 | A prospective study of surgeon -performed u ltrasound as the primary adjuvant modality for injured patient assessment. J Trauma 39: 492–500 | I | Assessment of surgeon -performed US in 371 patients (295 blunt / 76 penetrating). US is an accurate modality (81.5% sensitivity; 99.7% specificity) which may be performed by surgeons. Recommend repeat US at 12 -14 hrs if initial exam is negative. |

| Thomas B | 1997 | Ultrasound evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma: program implementation, initial experience, and learning curve.J Trauma 42: 384–390 | I | US examination s performed in 300 patients by surgeons and trauma fellows with review of false( -) and false(+) by radiologist. Demonstrated 81.0% sensitivity and 99.3% specificity. Accuracy plateaus after 100 examinations. Projected cost savings of $41,000. |

| McKenney MG | 1998 | Can surgeons evaluate emergency ultrasound scans for blunt abdominal trauma? J Trauma 44: 649-653 | I | Prospective study of 112 FAST examinations performed and initially interpreted by surgeons with final interpretation by radiologist. No false negat ives, 2 false positives recorded. Good agreement between interpretation by surgeon and radiologist (99%). |

| Jacob ET | 1979 | Discriminate diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal injuries: accuracy and hazards.Am Surgeon 45: 11-14 | II | DPL 93.4% accurat e in prediction of positive exploratory laparotomy and 96.6% accurate in prediction of negative exploratory laparotomy in patients with mile or equivocal clinical findings. |

| Butterworth JF | 1980 | Detection of occult abdominal trauma in patients with severe h ead injuries.Lancet 2: 759-762 | II | DPL recommended for trauma patients who are unable to obey simple commands secondary to closed head injury to exclude occult intra -abdominal injury. |

| Alyono D | 1982 | Reappraisal of diagnostic peritoneal lavage criteria for operation in penetrating and blunt trauma.Surgery 92: 751-757 | II | In blunt trauma, the highest level of accuracy is achieved with standard diagnostic criteria: DPL -RBC > 100K/mm3; DPL-WBC > 500/mm3 |

| Kusminsky RE | 1982 | The potential value of endotoxin -amylas e detection in peritoneal lavage fluid.Am Surgeon 48: 359-362 | II | Detection of amylase or endotoxin in DPL fluid is valuable in the detction of pancreatic and gastrointestinal injuries. |

| Rodriguez A | 1982 | Recognition of intra -abdominal injury in blunt traum a victims. A prospective study comparing physical examination with peritoneal lavage.Am Surgeon 48: 457-459 | II | Findings on PE unreliable in conscious, oriented patients with BAT resulting in potential for missed intra -abdominal injuries. DPL highly accu rate and sensitive for detection on inta -abdominal injuries. |

| Kuminsky RE | 1984 | The value of sequential peritoneal profile in blunt abdominal trauma.Am Surgeon 50: 248-253 | II | Addition of endotoxin in DPL fluid allows safe non -operative management in hemody namically stable BAT patients with DPL RBC count > 100K/mm3. |

| Davis RA | 1985 | The use of computerized axial tomography versus peritoneal lavage in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. Surgery 98: 845-850 | II | High sensitivity and specificity documented fo r DPL compared with CT in BAT: cost of CT 8x cost of DPL. CT as the sole diagnostic modality in hemodynamically stable patients with BAT adds cost, time and risk of missed injury without providing significant additional information. |

| Peitzman AB | 1986 | Prospective study of computed tomography in initial management of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 26: 585-592 | II | CT demonstrated to by highly sensitive (97.6%) and specific (98.7%) for the diagnosis of intra -abdominal injuries in hemodynamically stable patie nts. CT permits safe non -operative management of solid visceral injuries. |

| Gomez GA | 1987 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the management of blunt abdominal trauma: a reassessment. J Trauma 27: 1-5 | II | DPL is an accurate indicator of significant intra -abdomi nal injury as documented by exploratory laparotomy in patients with BAT. |

| Pagliarello G | 1987 | Abdominopelvic computerized tomography and open peritoneal lavage in patients with blunt abdominal trauma: a prospective study.Can J Surgery 30: 10-13 | II | CT less sensitive when compared with DPL. Agreement between DPL and CT demonstrated in 53%. DPL superior to CT for evaluation of BAT. |

| Chambers JA | 1988 | Ultrasound in abdominal trauma: an alternative to peritoneal lavage.Arch Emerg Med 5: 26-33 | II | US is a reliab le diagnostic technique for detection of free intraperitoneal fluid but is unreliable for grading specific injuries. |

| Frame S | 1989 | Computed tomography versus diagnostic peritoneal lavage: usefulness in immediate diagnosis of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 18: 513-516 | II | DPL safer and more accurate than CT in the evaluation of BAT. |

| Gruessner R | 1989 | Sonography versus peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 29: 242-244 | II | Ultrasound preferred initial screening method compared to DPL for evaluation of BAT. However, DPL has complementary role in the presence of indeterminate US. |

| Mckersie RC | 1989 | Intra-abdominal injury following blunt trauma. Identifying the high -risk patient using objective risk factors.Arch Surgery 124: 809-813 | II | Presence of (1) chest injury; (2) base deficit < -3.0; (3) hypotension on arrival; (4) prehospital hypotension; (5) pelvis fracture significantly correlated with intra -abdominal injury. DPL, US, or CT recommended in the presence of one of these risk factors. |

| Meyer DM | 1989 | Evaluation of computed tomography and diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 29: 1168-1170 | II | CT scan significantly less sensitive than DPL in BAT patients with equivocal findings on PE (74.3% vs 95.9%). CT unreliab le for identification of small intestinal injuries in the acute stage of evaluation. |

| Cue JI | 1990 | A prospective, randomized comparison between open and closed peritoneal lavage techniques.J Trauma 30: 880-883 | II | Open DPL takes longer to perform with bette r return of lavage fluid. Time consideration and improved patient tolerance justifies use of closed CPL. |

| Lopez-Viego MA | 1990 | Open versus closed diagnostic peritoneal lavage in the evaluation of abdominal trauma. Am J Surgery 160: 594-596 | II | Open DPL has fewer complications. Because it may be performed faster, closed DPL is recommended with conversion to open technique if complications occur. |

| Bilge A | 1991 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. Eur J Surgery 157: 449-451 | II | DPL is highly accurate for the diagnosis of free intraperitoneal blood, but is overly sensitive in that it is unable to distinguish clinically unimportant amounts of intraperitoneal blood. Recommend additional diagnostic studies in hemodynamically stable patients with BAT to reduce incidence of unnecessary laparotomies. |

| Drost TF | 1991 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Limited indications due to evolving concepts in trauma care. Am Surgeon 57: 126-128 | II | Non-therapeutic exploratory laparotomy performed in 1/3 BAT patients based on DPL results. (+)DPL not a reliable predictor of significant intra -abdominal injury, especially in lieu of non -operative management protocols. |

| Hoffmann R | 1992 | Blunt abdominal trauma in cases of multiple trauma evaluated by ultrasonography: a pros pective analysis of 291 patients.J Trauma 32: 452-458 | II | Documented high sensitivity (89%) and specificity (97%) for US in patients with ISS > 20. False negative results limited by surveillance of indeterminate US with DPL, CT, or exploratory laparotomy. |

| Boulanger BR | 1993 | The clinical significance of acute hyperamylasemia after blunt trauma.Can J Surgery 36: 63-69 | II | Admission serum amylase levels should not by used to determine clinical or radiographic evaluation of patients with BAT. |

| Forster R | 1993 | Ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma: influence of the investigators’ experience.J Trauma 34: 264-269 | II | US performed by surgeons has high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (95%) with a short learning phase. |

| Jaffin JH | 1993 | Alkaline phosphatase levels in diagnostic peritoneal lavage fluid as a predictor of hollow visceral injury.J Trauma 34: 829-833 | II | Routine measurement of alkaline phosphatase in DPL fluid is not cost-effective. |

| Glaser K | 1994 | Ultrasonography in the management of blunt abdominal and thoracic trauma. Arch Surgery 129: 743-747 | II | Retrospective review of US performed as the initial diagnostic modality in 1151 patients. US provides results similar to CT and DPL (99% sensitivity; 98% specificity) at less cost and without complications. US inaccurate in diagnosis of small bowel perforations. |

| Ma OJ | 1995 | Evaluation of hemoperitoneum using a single - vs multiple -view ultrasonographic examination.Acad Emerg Med 2: 581-586 | II | Comparison of single -view (right intercostal oblique) with multiple -view US. Sensitivity greater with multiple -view US (87% vs 51%). Specificity 100% with both techniques. |

| Nagy KK | 1995 | Aspiration of free blood from the peritoneal cavity does not mandate immediate laparotomy.Am Surgeon 61: 790-795 | II | Comparison of aspi ration of gross blood on DPL to actual clinical results in 566 patients who sustained blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Aspiration of < 5 ml free blood associated with > 20% non -therapeutic laparotomy rate. |

| Boulanger BR | 1995 | A prospective study of emergent abdominal sonography after blunt trauma. J Trauma 39: 325-330 | II | Comparison of US with DPL and CT for detection of intraperitoneal fluid. US performed in mean time of 2.6 mins with 81% sensitivity, 98% specificity and 96% accuracy. US is a rapid , accurate examination for initial evaluation of free intraperitoneal following BAT. |

| Boulanger BR | 1996 | Emergent abdominal sonography as a screening test in a new diagnostic algorithm for blunt trauma.J Trauma 40: 867-874 | II | Description of a diagnostic al gorithm using US in BAT. Documented 94% accuracy in 400 patients studied; US exam completed in < 3 mins (82%). US is a rapid and accurate diagnostic modality. |

| Gow KW | 1996 | Validity of visual inspection of diagnostic peritoneal lavage fluid.Can J Surgery 39: 114-119 | II | Determine predictive value of visual inspection of DPL fluid for identification of intra -abdominal injury. Visual inspection found to have good NPV (98.9%) but poor PPV (52.0%). Hemodynamically stable patients with (+)DPL by visual inspe ction should have fluid tested before exploratory laparotomy. |

| Healy MA | 1996 | A prospective evaluation of abdominal ultrasound in blunt trauma: Is it useful? J Trauma 40: 875-883 | II | Assessment of accuracy of technician -performed US in evaluation of 796 pati ents with BAT. US demonstrated 88.2% sensitive, 97.7% specific, 72.3% PPV and 99.2% NPV. Accuracy of US consistent with other diagnostic modalities. |

| McKenney MG | 1996 | 1000 consecutive ultrasounds for blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 40: 607-610 | II | Assessment of utility of US in patients with indications for DPL or CT. US demonstrated 88% sensitivity, 99% specificity, 97% accuracy. (+)US in hemodynamically unstable patients or in the presence of decreasing hematocrit mandates exploratory laparotomy. CT scan following (+)US in hemodynamically stable patients permits selection for non -operative management. |

| Branney SW | 1997 | Ultrasound based key clinical pathway reduces the use of hospital resources for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 42: 1086-1090 | II | Prospective, non -randomized study of US protocol for evaluation of BAT compared with retrospective controls using CT and DPL. Decreased use of DPL and CT by 74% and 58% respectively without missed injuries. US safe and cost -effective diagno stic modality for evaluation of BAT. |

| McElveen TS | 1997 | The role of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma: a prospective study.Am Surgeon 63: 184-188 | II | Comparison of surgeon -performed US to CT and DPL in 82 patients with BAT. Ultrasound found to be 8 8% sensitive, 98% specific, 96% accurate; NPV = 97%, positive predictive value (PPV) = 93%. US accurate and may be performed with minimal training. |

| Blow O | 1998 | Speed and efficiency in the resuscitation of blunt trauma patients with multiple injuries: the advantage of diagnostic peritoneal lavage over abdominal computed tomography.J Trauma 44: 287-290 | II | Sensitivity and specificity of DPL similar to CT scan in patients with hemodynamic instability, severe TBI or multiple injuries. DPL is more efficient a nd may be performed with lower cost. |

| Livingston DH | 1998 | Admission or observation is not necessary after a negative abdominal computed tomographic scan in patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma: results of a prospective, multi -institutional trial.J Trauma 44: 273-282. | II | Study demonstrates 99.63% negative predictive value (NPV) for CT scan performed in 2774 patients following blunt abdominal trauma (BAT). CT scan detected 22/25 hollow visceral injuries. Patients with (-) CT scan may be safely discharged. |

| Fischer RP | 1978 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: fourteen years and 2,586 patients later.Am J Surgery 136: 701-704 | III | Organ-specific accuracy of DPL documented for spleen (98.5%), liver (97.1%), small bowel (91.3%), intraperitoneal bladder (66. 7%), and diaphragm (59.1%). Compared with historical controls, DPL decreased rate of unnecessary laparotmy from 13% to 6% and decreased mortality from 46.4% to 30%. Decreased mortality presumed due to decreased incidence of missed injury with clinical observation alone. |

| Hubbard SG | 1979 | Diagnostic errors with peritoneal lavage in patients with pelvic fractures. Arch Surgery 114: 844-846 | III | Accuracy of DPL significantly reduced in the presence of a pelvis fracture. Additional diagnostic tests recommended in hemodynamically stable patients with pelvis fracture and (+)DPL. |

| Bagwell CE | 1980 | Blunt abdominal trauma: exploratory laparotomy or peritoneal lavage?Am J Surgery 140: 368-373 | III | DPL should be considered mandatory in hemodynamically stable patients w ith altered mental status or multiple injuries. |

| Robbs JV | 1980 | Blunt abdominal trauma with jejunal injury: a review.J Trauma 20: 308-311 | III | Clinical findings of pain, tenderness, guarding, absent bowel sounds, and hypovolemia correlate with jejunal injur y. Parascentesis (i.e. four -quadrant aspiration) recommended in patients with multiple injuries, concomitant closed head injury, or impaired level of consciousness. If parascentesis is negative, DPL is indicated. |

| Sherwood R | 1980 | Minilaparoscopy for blun t abdominal trauma. Arch Surgery 115: 672-673 | III | Mini-laparoscopy allows direct visualization of the extent and source of hemorrhage in BAT patients with (1) altered sensorium, (2) multi-system trauma, (3) unexplained hypotension, or (4) equivocal finding s on PE. In addition, the clinical importance of intra-abdominal hemorrhage may be determined. |

| Ward RE | 1981 | Study and management of blunt trauma in the immediate post -impact period.Rad Clin NA 19: 3-7 | III | Splanchnic angiography should be considered as a complement to DPL in patients with (1) pelvis fractures, (2) indications for thoracic aortography, and (3) perplexing abdominal findings. |

| Alyono D | 1982 | Significance of repeating diagnostic peritoneal lavage.Surgery 91: 656-659 | III | Repeat DPL performed a t 1-2 hrs has a high degree of sensitivity, specificity and accuracy in patients with indeterminate initial DPL (i.e. DPL-RBC = 50-100 K/mm3; DPL-WBC = 100-500/mm3). |

| Smith SB | 1982 | Abdominal trauma: the limited role of peritoneal lavage.Am Surgeon 48: 514-517 | III | High degree of accuracy demonstrated with PE in patients capable of a reliable PE. DPL is very sensitive and is associated with a high non-therapeutic laparotmy rate |

| Berci G | 1983 | Emergency minilaparoscopy in abdominal trauma. An update. Am J Surgery 146: 261-265 | III | Laparoscopy safer, faster, and more accurate than DPL. Identification of intra -abdominal blood without an identified injury permits non -operative management and decreases the rate of unnecessary exploratory laparotomies. |

| Burney RE | 1983 | Diagnosis of isolated small bowel injury following blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Emerg Med 12: 71-74 | III | Abdominal pain was a universal symptom in patients who communicate. Other predictive findings on PE included diffuse abdominal tenderness, abdomina l rigidity, and absence of bowel sounds. DPL was the most sensitive diagnostic modality for small bowel injury. |

| Soderstrom CA | 1983 | The diagnosis of intra -abdominal injury in patients with cervical cord trauma. J Trauma 23: 1061-1065 | III | All significant i ntra-abdominal injuries diagnosed by DPL in patients with cervical cord injuries. Recommend DPL to exclude intra -abdominal injury in BAT patients with concomitant cervical cord injuries. |

| Berry TK | 1984 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt trauma patients with coagulopathy.Ann Emerg Med 13: 879-880 | III | Accuracy of DPL not diminished by presence of coagulopathy. Exploratory laparotomy is indicated in patients with (+)DPL with post-traumatic coagulopathy. |

| Mustard RA | 1984 | Blunt splenic trauma: diagnosis an d management.Can J Surgery 27: 330-333 | III | DPL diagnostic in 86 patients with splenic injury documented by exploratory laparotomy. |

| McLellan BA | 1985 | Analysis of peritoneal lavage parameters in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 25: 393-399 | III | Based on sign ificant number of therapeutic laparotoomis, DPL RBC count > 20K/mm3recommended as indication for exploratory laparotomy. |

| Trooskin SZ | 1985 | Peritoneal lavage in patients with normal mentation and hematuria after blunt trauma. S,G & O 160: 145-147 | III | DPL reveals injuries which require surgery in 45% of BAT patients with normal mentation and hematuria. DPL recommended in patients with BAT who present with hematuria in the presence of normal neurologic examination. |

| Van Dongen LM | 1985 | Peritoneal lavage in cl osed abdominal injury.Injury 16: 227-229 | III | DPL may be overly sensitive in evaluation of BAT. |

| Webster VJ | 1985 | Abdominal trauma: pre -operative assessment and postoperative problems in jntensive care.Anaest & Int Care 13: 258-262 | III | CT scan has signific antly impacted the use of other diagnostic modalities in the evaluation of hemodynamically stable patients with BAT. |

| Ryan JJ | 1986 | Critical analysis of open peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma.Am J Surgery 151: 221-223 | III | False positive rate for peritoneal lavage higher than previously reported (sensitivity = 83%) resulting in 27% non -therapeutic laparotomy rate. |

| Kane NM | 1987 | Efficacy of CT following peritoneal lavage in abdominal trauma.J Comp Asst Tomo 11: 998-1002 | III | CT revealed substantial intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries in 1/3 patients who underwent CT following DPL. CT recommended when clinical status equivocal regardless of DPL results. |

| Pattyn P | 1989 | Peritoneal lavage after abdominal trauma: indications, technique, results. Int Surgery 74: 17-19 | III | Based on high sensitivity (false negative rate = 1%) and low incidence of complications (0.5%), DPL recommended for the evaluation of BAT. |

| Wening JV | 1989 | Evaluation of ultrasound, lavage, and computed tomography in blunt abdomina l trauma. Surg Endoscopy 3: 152-158 | III | Demonstrated 84% sensitivity and 97% specificity for US in evaluation of BAT. US is a reliable, fast and repeatable diagnostic modality. |

| Ceraldi CM | 1990 | Computerized tomography as an indicator of isolated mesenteri c injury. A comparison with peritoneal lavage.Am Surgeon 561: 806-810 | III | Sensitivity of CT inadequate to reliably exclude mesenteric injury. DPL recommended as a more sensitive diagnostic modality. |

| D’Amelio LF | 1990 | A reassessment of the peritoneal lavage leukocyte count in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 30: 1291-1293 | III | Elevated DPL fluid WBC count (> 500/mm3) has on diagnostic value in the early (< 4 hrs) post -injury period. Isolated elevation of DPL WBC count may be more useful in delayed setting or in the presence of equivocal PE. |

| Davis JW | 1990 | Complications in evaluating abdominal trauma: diagnostic peritoneal lavage versus computerized axial tomography.J Trauma 30: 1506-1509 | III | Significantly lower complication rate for DPL compared to CT sca n (0.9% vs 3.4%) with no difference in preventable deaths. |

| Henneman PL | 1990 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: accuracy in predicting necessary laparotomy following blunt and penetrating trauma.J Trauma 30: 1345-1355 | III | Semi-open DPL 96% accurate for predict ion of need for exploratory laparotomy in BAT and 92% accurate in the presence of pelvic fracture. |

| Hawkins ML | 1990 | Is diagnostic peritoneal lavage for blunt trauma obsolete? Am Surgeon 56: 96-99 | III | Ease, safety (1% complication rate) and accuracy of DPL (97%) justify continued use in evaluation of BAT. |

| Jacobs DG | 1990 | Peritoneal lavage white count: a reassessment. J Trauma 30: 607-612 | III | Isolated elevation of DPL WBC count > 500/mm3not specific for diagnosis of intra -abdominal injury. Specificity incr eases with repeat DPL. |

| Lang EK | 1990 | Intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal organ injuries diagnosed on dynamic computed tomograms obtained for assessment of renal trauma. J Trauma 30: 1161-1168 | III | CT scan helpful in the diagnosis of unsuspected abdominal or retroperitoneal injuries in the evaluation of patients for renal trauma. Patients with ( -)CT may be safely observed. |

| Matsubara TK | 1990 | Computed tomography of abdomen (CTA) in management of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 30: 410-414 | III | CT is a valuabl e diagnostic modality in hemodynamically stable patients with BAT if performed correctly and interpreted accurately. Patients with ( -)CT should be admitted for observation. |

| Megison SM | 1990 | The value of alkaline phosphatase in peritoneal lavage.Ann Emerg Med 19: 503-505 | III | Measurement of alkaline phosphatase in DPL fluid adds no diagnostic advantage in identification of intestinal injury. |

| Soyka JM | 1990 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: is an isolated WBC count greater than or equal to 500/mm 3 predictive of intra-abdominal injury requiring celiotomy in blunt trauma patients?J Trauma 30: 874-879 | III | Isolated elevation of DPL WBC count > 500/mm3should not be an indication for exploratory laparotomy in BAT. |

| Barba C | 1991 | Is positive diagnostic peritoneal lava ge an absolute indication for laparotomy in all patients with blunt trauma? Can J Surgery 34: 442-445 | III | Immediate exploratory laparotomy not necessarily mandasted in the presence of (+)DPL. Additional diagnostic studies should be considered in hemodynam ically stable patients with (+)DPL. |

| Berci G | 1991 | Emergency Laparoscopy.Am J Surgery 161: 332-335 | III | Diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) is a viable diagnostic modality in the evaluation of BAT. DL lowers incidence of non -therapeutic exploratory laparotomy. |

| Davis JW | 1991 | Base deficit as an indicator of significant abdominal injury.Ann Emerg Med 20: 842-844 | III | Base deficit (BD) < - 6.0 is a sensitive indicator of intra -abdominal injury in BAT. DPL or CT recommended for patients with BD < - 6.0. |

| DeMaria EJ | 1991 | Management of patients with indeterminate diagnostic peritoneal lavage results following blunt trauma.J Trauma 31: 1627-1631 | III | Indeterminate DPL correlates with injuries that may be managed non-operatively. CT recommended following indete rminate DPL rather than repeat DPL. |

| Fryer JP | 1991 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage as an indicator for therapeutic surgery.Can J Surgery 34: 471-476 | III | Sixty-five percent (65%) of patients who underwent exploratory laparotomy for (+) DPL had therapeutic lap arotmies. |

| McAnena OJ | 1991 | Contributions of peritoneal lavage enzyme determinations to the management of isolated hollow visceral abdominal injuries.Ann Emerg Med 20: 834-837 | III | Elevation of DPL fluid amylase is highly specific for isolated small bowel i njury. Recommend routine enzyme determinations for DPL effluent as a marker for small bowel injury. |

| McAnena OJ | 1991 | Peritoneal lavage enzyme determinations following blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma.J Trauma 31: 1161-1164 | III | Elevated amylase and alkaline phosphatase levels in DPL fluid increases index of suspicion for presence of a small bowel injury in patients with ( -)DPL by RBC count. |

| Mure AJ | 1991 | Serum amylase determination and blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surgeon 57: 210-213 | III | Serum amylase has poor sensitivity, specificity and PPV for the diagnosis of intra -abdominal injury. Routine serum amylase has no value in the evaluation of BAT. |

| Perez FG | 1991 | Evaluation of the abdomen in intoxicated patients: is computed tomography scan or peritoneal lavage always indicated?Ann Emerg Med 20: 500-502 | III | Legally intoxicated patients with normal mentation may be reliably assessed by physical examination. Elevated serum ethanol does not mandate CT or DPL. |

| Sahdev P | 1991 | Evaluation of liver function tes ts in screening for intra -abdominal injuries.Ann Emerg Med 20: 838-841 | III | Elevated liver function tests associated with injury to the liver. Patients with elevated liver function tests should undergo CT scan. |

| Day AC | 1992 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: integration with clinical information to improve diagnostic performance.J Trauma 32: 52-57 | I | Combination of clinical evaluation and DPL reduces rate of non -therapeutic laparotomies, but increases the number of missed injuries. The highest accuracy (95%) i s obtained by combination of circulatory assessment and DPL. |

| Driscoll P | 1992 | Diagnostic peritoneal lavage: it’s red but is it positive?Injury 23: 267-269 | III | Visual assessment of DPL fluid RBC -count inaccurate. |

| Knudson MM | 1992 | Hematuria as a predictor o f abdominal injury after blunt trauma.Am J Surgery 164: 482-485 | III | Hematuria is a marker for renal or extra -renal intra -abdominal injury. CT recommended in the presence of hematuria with shock. |

| Pattimore D | 1992 | Torso injury patterns and mechanisms in c ar crashes: an additional diagnostic tool.Injury 23: 123-126 | III | Injuries to the spleen, liver, pelvis and aorta more likely with side impact compared to front impact collisions. |

| Wyatt JP | 1992 | Variation among trainee surgeons in interpreting diagnostic p eritoneal lavage fluid in blunt abdominal trauma. J Royal Coll Surg (Edin) 37: 104-106 | III | Estimation of DPL RBC -count by visual inspection inaccurate compared to microscopic analysis. Recommend quantitative cell count vs visual assessment of DPL fluid to make decision on management. |

| Baron BJ | 1993 | Nonoperative management of blunt abdominal trauma: the role of sequential diagnostic peritoneal lavage, computed tomography, and angiography.Ann Emerg Med 22: 1556-1562 | III | Combined modalities of CT scan and an giography in hemodynamically stable patients with (+)DPL reduces the non -therapeutic laparotomy rate. |

| Bode PJ | 1993 | Abdominal ultrasound as a reliable indicator for conclusive laparotomy in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 34: 27-31 | III | US demonstrated hi gh sensitivity (92.8%) and specificity (100%). Routine US recommended for 1) abdominal findings not initially felt to warrant immediate laparotomy, 2) equivocal results on initial US, 3) deteriorating clinical situation. |

| Visvanathan R | 1993 | Blunt abdomina l trauma - injury assessment in relation to early surgery.J Royal Coll Surg (Edin) 38: 19-22 | III | DPL highly sensitive (95%) with 81% specificity and 89% accuracy. Combination of DPL and US facilitates early assessment and management of abdominal injuries . |

| Mendez C | 1994 | Diagnostic accuracy of peritoneal lavage in patients with pelvic fractures. Arch Surgery 129: 477-481 | III | Registry study of 286 open DPLs performed in patients with BAT in the presence of a pelvis fracture. Open DPL accurate modality (94% sensitivity; 99% specificity) for evaluation of patients with multiple injuries, including pelvis fractures. |

| Tibbs PA | 1980 | Diagnosis of acute abdominal injuries in patients with spinal shock: value of diagnostic peritoneal lavage.J Trauma 20: 55-57 | III | DPL recommended for exclusion of intra -abdominal injuries in spinal cord injured patients with complete neurologic deficit. |

| Baron BJ | 1993 | Nonoperative management of blunt abdominal trauma: the role of sequential diagnostic peritoneal lavage, computed tomo graphy, and angiography.Ann Emerg Med 22: 1556-1562 | III | Combined modalities of CT scan and angiography in hemodynamically stable patients with (+)DPL reduces the non -therapeutic laparotomy rate. |

| Mendez C | 1994 | Diagnostic accuracy of peritoneal lavage in patients with pelvic fractures. Arch Surgery 129: 477-481 | III | Registry study of 286 open DPLs performed in patients with BAT in the presence of a pelvis fracture. Open DPL accurate modality (94% sensitivity; 99% specificity) for evaluation of patients wit h multiple injuries, including pelvis fractures. |

| Grieshop NA | 1995 | Selective use of computed tomography and diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma.J Trauma 38: 727-731 | III | Registry review of 956 hemodynamically stable patients with reliabl e neurologic examinations (GCS > 11). Patients with abnormal PE, chest injury or gross hematuria have high incidence of intra-abdominal injury which require exploratory laparotomy. No CT required in patients with normal PE, no chest injury and no hematur ia. Elevated blood alcohol does not alter accuracy of PE. |

| Nolan BW | 1995 | Mesenteric injury from blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surgeon 61: 501-506 | III | Review of 27 patients with mesenteric injury following BAT. CT performed in 10 patients; failed to detect m esenteric injury in 7. High index of suspicion required to identify patients with mesenteric injury. CT scan is insufficient diagnostic modality for this injury and may result in missed injuries to mesentery and small bowel. |

| Chandler CF | 1997 | Seatbelt si gn following blunt trauma is associated with increased incidence of abdominal injury.Am Surgeon 63: 885-888 | III | Evaluation of seatbelt sign (SBS) as predictor of intra -abdomial injury in 14 patients. Sensitivity for solid visceral injuries was 85% and 100% with CT can and DPL respectively; sensitivity for hollow visceral injuries was 33% and 100% respectively. Negative CT scan in patients with SBS mandates admission and observation. Free fluid on CT scan warrants further investigation (i.e. DPL or explo ratory laparotomy). |

| Kern SJ | 1997 | Sonographic examination of abdominal trauma by senior surgical residents. Am Surgeon 63: 669-674 | III | Evaluation of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) following PE in 518 patients (92.4% blunt / 7.6% penetrating ). FAST examination 73.3% sensitive, 97.5% specific with 98.3% NPV and 96.1% PPV. Low sensitivity due to missed hollow visceral injuries. |

| McKenney KL | 1997 | Cost reduction using ultrasound in blunt abdominal trauma. Emerg Radiology 4: 3-6 | III | Comparison of 626 patients (Group 1) evaluated with CT and DPL with 564 patients (Group 2). Use of DPL and CT decreased by 94% and 63% respectively in Group 2. Decreased cost / patient by $170. Recommend US as the initial diagnostic test of choice in BAT with unreliable PE. US replaces DPL and allows more resource-efficient use of CT scan. |

| Porter RS | 1997 | Use of ultrasound to determine need for laparotomy in trauma patients. Ann Emerg Med 29: 323 -330 | III | Retrospective review of technician -performed US in 1631 pati ents without controls. Sensitivity and specificity of US 93% and 90% respectively. US safe and cost -effective diagnostic modality in the evaluation of BAT. |

| Schurink GW | 1997 | The value of physical examination in the diagnosis of patients with blunt abdomi nal trauma: a retrospective study.Injury 28: 261-265 | III | Retrospective study of physical examination (PE) in 204 patients with BAT. Patients with isolated TBI, low -impact rib pain, isolated abdominal trauma may be evaluated with PE plus ultrasound (US) with > 85% NPV. Higher incidence of intra -abdominal injury in the presence of low rib fractures and high -energy impact, therefore follow-up CT scan recommended in presence of normal US. |

| Sherbourne CD | 1997 | Visceral injury without hemoperitoneum: a limitati on of screening abdominal sonography for trauma. Emerg Radiology 4: 349-354 | III | Review of 196 patients with intra -abdominal injury; 50/196 (26%) had no hemoperitoneum. Fifteen of 50 patients had ( -)FAST examination. US may fail to detect intra -abdominal injuries in the absence of hemoperitoneum. |

| Takishima T | 1997 | Serum amylase level on admission in the diagnosis of blunt injury to the pancreas.Ann Surgery 226: 70-76 | III | Serum amylase elevated in 84% of patients with pancreatic injury at presentation; ele vated in 76% (< 3 hrs post -injury) and 100% (> 3 hrs post-injury). Serum amylase must be measured at least 3 hrs post-injury to avoid missed injuries. |

| Buzzas GR | 1998 | A comparison of sonographic examinations for trauma performed by surgeons and radiologis ts.J Trauma 44: 604-608 | III | Comparison of FAST performed by surgical residents (Group A) and US technicians/radiologists (Group B). Sensitivity 73.3% and 79.5% for Group A and B respectively. Specificity 97.5% and 99.3% for Group A and B respectively. Sensitivity improved with exclusion of hollow visceral injuries. |

| Smith SR | 1998 | Institutional learning curve of surgeon-performed trauma ultrasound. Arch Surg 133: 530-536 | III | Sensitivity and specificity of FAST examination 73% and 98% respectively and may be learned without significant learning curve. Modality unreliable for detection of hollow visceral injuries. |